HOW TO FORGE A TRADITIONAL SAMURAI SWORD (KATANA)

In the Japanese Middle Ages, forging a Katana was not merely a technical process but a deeply spiritual practice. Ancient blacksmiths believed that creating a new sword involved invoking benevolent spirits to bless the blade. Before beginning the forging process, the swordsmith would perform purification rituals, chanting prayers to cleanse the workshop and prepare for the sacred task ahead. These ceremonies were crucial in ensuring that the resulting Katana would embody the Samurai spirit and serve as a symbol of honor and courage.

The Tatara: Crafting the Heart of the Steel

The journey of creating a Katana begins with building a unique type of furnace called a Tatara. This traditional smelting furnace, resembling a rudimentary clay blast furnace, is specially constructed for producing the raw material necessary for the blade. The Tatara is fueled with charcoal and iron sand, and the smelting process lasts for an exhaustive three days and three nights. During this time, the charcoal and iron sand are continuously fed into the furnace, maintaining the intense heat required to create the steel.

The ancient Japanese blacksmiths faced a significant challenge: the quality of the raw materials. Unlike the rich iron ore deposits found in the West, Japanese iron sand was low in purity. This made the smelting process particularly demanding, as it required advanced techniques to purify the metal. By controlling the temperature and airflow precisely, the craftsmen managed to separate impurities from the iron, allowing the creation of high-quality steel despite the raw material's limitations.

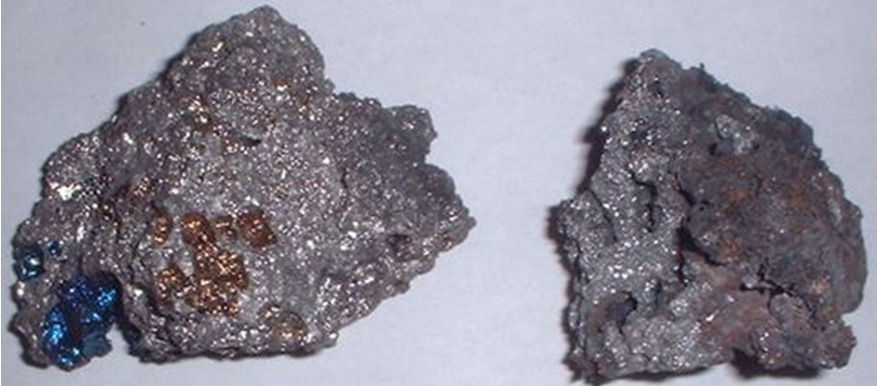

Tamahagane: The Jewel of Steel

The primary product of the Tatara is Tamahagane, which translates to "steel jewel". This material is the heart of a Katana, characterized by its porous texture and the unique combination of iron and carbon. However, even after smelting, the Tamahagane still contains impurities. The initial smelting process creates a brittle, uneven block, which must be refined further before it can be shaped into a blade.

The raw Tamahagane is then broken into smaller pieces and sorted based on carbon content and hardness. The blacksmith selects the most suitable fragments for the blade, while the less refined portions are set aside for use in less critical components or modified by adding sections of purer Tamahagane to adjust the carbon content.

Refining the Steel: Purity Through Folding

Once the best Tamahagane pieces are selected, the refining process begins. The steel is heated to a red-hot state and then hammered repeatedly to eliminate excess impurities. During this phase, the steel is folded and hammered multiple times—often as many as 10 to 15 folds—to create thousands of layers. This folding technique serves a dual purpose: it evens out the carbon distribution and improves the blade’s resilience.

Folding also gives rise to the characteristic Hada (grain pattern) on the blade, a hallmark of traditional Japanese craftsmanship. The repetitive hammering and folding not only strengthen the steel but also create a beautiful, wood-like pattern that distinguishes authentic handcrafted Katanas from mass-produced replicas.

Crafting the Core and Outer Layer

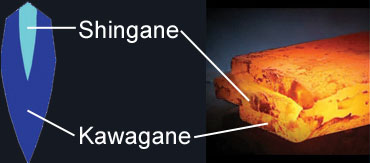

A true Katana is known for its dual steel construction: a hard outer layer for sharpness and a softer inner core for flexibility. To achieve this, the swordsmith carefully layers the Kawagane (outer steel) and Shingane (core steel). The outer layer is crafted from high-carbon steel, providing the cutting edge, while the core is made from lower-carbon steel, allowing the blade to absorb shock without breaking.

The combination of these materials ensures that the Katana is both razor-sharp and exceptionally durable. The blacksmith folds the layered steel once again, meticulously welding the materials together through intense heat and precise hammering. This results in a blade that can withstand the rigors of combat while retaining its sharpness.

Symbolism and Mastery

Creating a Katana is more than just a mechanical process; it is an artistic and spiritual endeavor. The traditional forging method has been passed down through generations, each master swordsmith adding their unique touch while respecting ancient techniques. The final product is not just a weapon but a symbol of dedication, patience, and the Samurai code of honor.

Once the raw Tamahagane steel is produced through the intricate smelting process in the Tatara furnace, it still contains varying levels of carbon and impurities. To optimize the steel for crafting a Katana, the next crucial step is fragmentation and selection.

Fragmentation and Sorting

The solid block of Tamahagane is carefully broken down into small cubes. These fragments are then meticulously inspected, with each piece evaluated for its carbon content and purity. The skilled blacksmith can determine the quality of each fragment by assessing its color and texture. Pieces with a darker, more uniform hue typically indicate higher carbon content, making them ideal for creating the hard outer layer of the blade (Kawagane). Lighter, less dense fragments with lower carbon are better suited for the softer core (Shingane).

Heating and Hammering: Transforming Cubes into Sheets

After sorting, the chosen Tamahagane cubes are heated to a red-hot temperature. This intense heat makes the metal malleable, allowing it to be hammered into thin sheets. This stage requires both precision and expertise, as the hammering must be even and consistent to produce uniform sheets. The goal is to create thin, flat layers that can be stacked and folded later in the process.

The blacksmith constantly monitors the thickness and texture of the sheets, ensuring that they possess the desired characteristics: high hardness and minimal impurities for the outer layer, and greater flexibility and durability for the core. The sheets are cooled and reheated multiple times during this phase to maintain their structural integrity while reducing the risk of cracks or deformation.

Layering and Fusion

Once the Tamahagane sheets are prepared, they are layered strategically to form the Katana’s core and outer shell. The harder, carbon-rich sheets (Kawagane and Hagane) are placed on the outside, while the more pliable, low-carbon sheets (Shingane) form the inner layer. This combination creates a blade that is both resilient and sharp, capable of withstanding impact without chipping or breaking.

The stacked sheets are then heated once more and hammered together to fuse them into a single, cohesive billet. This fusion is critical because it not only binds the layers but also ensures that the carbon content is evenly distributed. The blacksmith must carefully control the temperature to prevent burning off too much carbon, which would compromise the blade’s hardness.

Forging the Billet: Creating the Blade’s Foundation

Once fused, the billet undergoes a process of folding and hammering. This step is repeated several times, with the billet folded upon itself to increase the number of layers exponentially. Each fold effectively doubles the layers, creating a structure with thousands of microscopic layers. This process not only enhances the blade’s durability but also contributes to the unique Hada (grain pattern) characteristic of high-quality Katanas.

Precision and Skill

The entire process of refining Tamahagane requires a keen eye and precise technique. The blacksmith’s experience is crucial for maintaining the ideal balance between hardness and flexibility, as improper handling can lead to brittleness or weak points in the finished blade. The final product of this meticulous process is a solid, layered billet that serves as the foundation for crafting the legendary Katana.

The process of forging a traditional Samurai Katana is an intricate and labor-intensive art, steeped in centuries of Japanese tradition. One of the most critical phases in the creation of a Katana is the repeated heating and hammering of the steel. This rigorous process is essential for purifying the metal, enhancing its structural integrity, and giving the blade its unique layered composition.

Repeated Heating and Hammering: The Foundation of Strength

To begin, the raw Tamahagane steel, previously smelted in the Tatara furnace, is heated until it reaches a red-hot, malleable state. The blacksmith then hammers the steel repeatedly, flattening and straightening it while simultaneously forcing out impurities. This process, known as forging, must be executed with precision. Too much force can crack the metal, while too little will fail to remove imperfections.

The process of heating and hammering is not a one-time action. It must be repeated numerous times, each session serving to further refine the steel. During each cycle, the block is heated to a glowing temperature and hammered flat. As the blacksmith works, the steel becomes progressively stronger and more resilient, as well as more homogeneous in texture.

The Folding Process: Creating the Layered Structure

Once the steel block has reached the desired consistency, the blacksmith prepares to fold the steel. This technique is crucial for creating the Katana's signature layered structure. After heating the block once again, the craftsman makes a precise incision at the midpoint, folding the steel in half. This action doubles the number of layers, effectively combining two halves into one.

The block is then reheated and hammered again, flattening it back to its original dimensions. This entire process—heating, folding, and hammering—is repeated around six to ten times. Each fold not only increases the number of layers exponentially but also compresses and strengthens the metal. By the end of this stage, the steel plank may contain thousands of micro-layers, each less than a millimeter thick.

Purifying the Steel: Expelling Impurities Through Repetition

With each fold, the carbon content of the steel becomes more evenly distributed, reducing brittleness and increasing flexibility. However, this process also poses a challenge: carbon loss. As the steel is repeatedly exposed to high temperatures, carbon molecules may burn off, diminishing the hardness of the blade. The blacksmith must skillfully balance the carbon levels to maintain a strong yet flexible blade.

The constant folding and hammering also push impurities to the surface, where they can be scraped away or removed. This refining process is essential for eliminating slag and excess carbon, which, if left embedded, could compromise the blade's durability and cutting efficiency.

Assembling the Core: Creating the Shingane

Once the forging and folding process is complete, the steel plank is cut into three sections. However, crafting a complete Katana requires four parts, so an additional piece is sourced from a separate billet. These four segments are stacked together, heated, and hammered once more to fuse them into a single piece. This fusion requires immense skill to ensure the layers are perfectly aligned.

Next, the blacksmith works on creating the Shingane (core steel). This core is made from lower carbon steel, making it more flexible and capable of absorbing shock. The Shingane is crafted by molding, folding, and hammering it approximately ten times. This step helps reduce impurities and achieve the desired softness.

Combining the Core and Outer Layers: The Heart of the Katana

With the Shingane prepared, the outer layer, known as Kawagane, is shaped into a U-shape to accommodate the inner core. The Shingane is carefully placed within this U-shaped piece, and the entire assembly is heated once more. The blacksmith then hammers the combined billet until the two components meld seamlessly.

This phase is particularly delicate. If the welding is not done correctly, the blade can develop weak points where the layers separate. Additionally, the beating technique must ensure that the Kawagane remains on the exterior, while the Shingane stays securely inside. Any disruption to this balance can compromise the blade’s structural integrity.

Precision Welding and Final Shaping

The next step is to shape the entire assembly into a preliminary blade form. The billet is heated once more and then drawn out, extending the length while maintaining the correct cross-sectional geometry. The blade is given its distinctive curvature (sori) during this stage, carefully shaped by controlling cooling rates and using precise hammer strikes.

The repeated forging and folding of the billet not only enhances the blade's strength but also creates a unique grain pattern (Hada) on the steel’s surface. This pattern is an aesthetic hallmark of a traditionally made Katana, showcasing the skill and craftsmanship of the swordsmith.

The Molecular Precision of Layering

Due to the multiple folding processes, the steel now contains thousands of ultra-thin layers. The finished product has a molecular-level composition, where each layer is only a few micrometers thick. This intricate structure contributes to the blade’s iconic sharpness and durability. The resulting blade is hard on the outside for superior edge retention and soft on the inside for flexibility—an essential balance that defines the quality of a true Katana.

The Final Fusion: Creating a Masterpiece

The final step involves heating and hammering the blade one more time to finalize the fusion of layers. The swordsmith ensures that the blade's edge alignment is precise, and the curvature is perfect. After this, the blade is allowed to cool gradually, setting the shape and solidifying the layered structure.

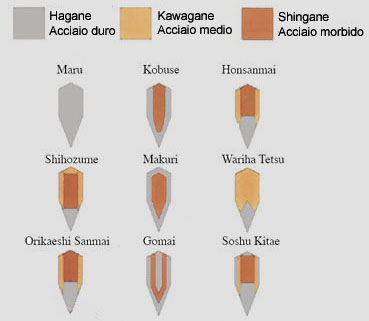

Advanced Techniques in Katana Forging: Combining Strength and Flexibility

The forging of a traditional Samurai Katana is a meticulous and intricate process, requiring not only skill but also deep knowledge of metallurgy. While the most straightforward method involves using Kawagane (leather-steel), which balances hardness and flexibility, more complex techniques often incorporate Hagane (blade-steel) to enhance the blade's sharpness and durability. These advanced methods reflect the evolution of sword-making in Japan, where master smiths constantly sought to improve the performance and longevity of their blades.

The Complexity of Using Hagane in Katana Forging

Unlike the relatively pliable Kawagane, Hagane is a high-carbon steel, making it significantly harder and more resistant to edge wear. However, this increased hardness also introduces a challenge: the steel becomes more brittle, making it prone to chipping or breaking if not properly tempered. Therefore, Hagane is often used in conjunction with other types of steel to create a blade that is both strong and resilient.

Layering Multiple Steel Types for Optimal Performance

To achieve the ideal balance, master swordsmiths often layered Hagane with Shingane (heart steel) and Kawagane. The Hagane forms the cutting edge due to its superior sharpness, while the softer Shingane serves as the core, absorbing shocks during combat. The Kawagane, typically positioned on the sides, adds flexibility and protects the inner core from damage.

This multi-layered construction is known as Sanmai or Kobuse forging technique. In these methods, the outer shell is made of hard steel (Hagane), while the core is softer, ensuring that the blade can withstand high-impact strikes without shattering. This combination of hardness and flexibility is crucial for maintaining the structural integrity of the Katana during rigorous use.

The Role of Legendary Swordsmiths: Masamune's Mastery

Throughout history, some of the most renowned Japanese swordsmiths, such as Masamune, pushed the boundaries of forging by using multiple types of steel within a single blade. It is said that Masamune, who is often regarded as the greatest swordsmith of Japan, could skillfully incorporate up to seven different steel types in one Katana. This complex layering technique resulted in blades that were exceptionally resilient and sharp, revered for their superior craftsmanship and legendary cutting ability.

These advanced techniques allowed the blade to feature differentiated hardness, meaning the cutting edge remained razor-sharp, while the spine and core retained flexibility. The combination made Masamune’s swords highly sought after, praised not only for their functionality in battle but also for their aesthetic beauty.

The Importance of the Kissaki: Crafting the Sword Tip

One of the most critical and challenging parts of forging a Katana is creating the Kissaki (tip). Due to its delicate and precise shape, the Kissaki must be exceptionally durable to withstand repeated impacts without dulling or breaking. Therefore, it is typically crafted using Hagane, as this high-carbon steel ensures a sharp and resilient edge.

The Kissaki is not merely a sharp point but a complex geometry that must seamlessly transition from the main blade. To achieve this, the swordsmith carefully layers the hard Hagane at the tip, blending it with the more flexible Kawagane to maintain structural consistency. This nuanced process requires a deep understanding of temperature control and hammering techniques to prevent cracking or distortion.

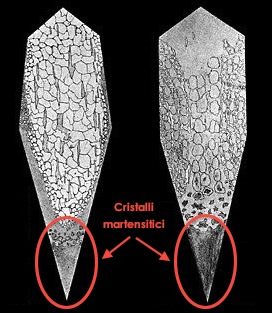

The Intricacies of Differential Hardening

Another vital aspect of creating a high-quality Katana is differential hardening, a process that enhances the blade's cutting performance while preserving its flexibility. The blade is coated with a layer of clay slurry, with a thicker layer applied to the spine and a thinner layer on the edge. This differential coating ensures that during quenching (rapid cooling), the edge cools faster than the spine, forming a hard martensitic crystal structure on the cutting edge while the spine remains softer and more ductile.

The result of this process is the formation of the Hamon (temper line), a visible, wavy pattern that marks the transition between hard and soft steel. The Hamon is not just decorative; it is a functional feature that highlights the blade's differentiated hardness. Skilled swordsmiths often craft the Hamon in artistic patterns, such as Suguha (straight), Gunome (wavy), or Choji (clove), showcasing their craftsmanship.

Advanced Layering Techniques: Shihozume and Orikata

While Sanmai and Kobuse are among the more commonly used techniques, some swordsmiths employed even more complex layering methods. For example:

-

Shihozume: A method where the core is completely encased in harder steel, offering superior protection while maintaining flexibility.

-

Orikata: A technique where the blade is folded in a specific way to create a double core, enhancing shock absorption without compromising the edge’s sharpness.

These advanced techniques require a precise balance between temperature control, hammering force, and layering accuracy. A slight mistake in any of these aspects can lead to structural weakness, resulting in a compromised blade.

Modern Interpretations: Blending Tradition with Technology

Today, modern swordsmiths continue to draw inspiration from these ancient methods, incorporating modern metallurgy to enhance the durability and cutting power of Katanas. Techniques such as vacuum forging and precision tempering allow for more consistent results while preserving the traditional aesthetic and functional qualities of the blade.

The Crucial Stage of Tempering: Hardening the Katana Blade

One of the most critical phases in crafting a traditional Samurai Katana is the tempering process. This stage is fundamental for giving the blade its renowned strength and durability, while also enhancing its flexibility. Tempering is a complex and delicate procedure that, if done incorrectly, can ruin even the most meticulously forged blade.

Shaping the Blade: Preparing for Tempering

Before tempering begins, the blade undergoes final shaping. At this stage, the swordsmith focuses on refining the Nakago (tang) and the Kissaki (tip). The Nakago serves as the base of the handle, and its shape must be precisely crafted to fit securely within the Tsuka (handle). The Kissaki, on the other hand, requires a balance of sharpness and strength, as it is often the point of initial impact during cuts.

The blade, still in its raw form, is heated again to a red-hot state. The swordsmith uses careful hammering to define the edge and tip, ensuring that the curvature remains consistent with the desired profile. Once the shape is complete, the blade is cooled slowly, allowing the structure to settle and minimizing stress before the tempering process begins.

Tempering: The Most Critical Moment

The tempering process involves rapidly cooling the heated blade to set its molecular structure. The Katana is heated to a red-hot glow and then quenched in water or oil. This sudden cooling is essential to harden the steel, but it is also extremely risky. The drastic temperature difference can cause cracks, splits, or warping.

Water vs. Oil Quenching: A Delicate Decision

The choice between water and oil as a cooling medium depends on the desired characteristics of the blade:

-

Water Quenching:

-

Typically used for high-carbon steel (Hagane).

-

Results in a very hard and sharp edge.

-

Higher risk of cracking due to the intense temperature change.

-

-

Oil Quenching:

-

More controlled cooling, reducing the risk of cracking.

-

Produces a softer edge, suitable for blades requiring greater flexibility.

-

-

Mixed Quenching:

-

In some cases, swordsmiths use a combination of oil and water, beginning the process with one and finishing with the other to balance hardness and flexibility.

-

During this critical phase, the blade’s molecular structure changes significantly. The iron atoms, initially arranged in a loose crystalline structure, begin to align with carbon atoms. The rapid cooling traps the carbon molecules within the iron matrix, forming a martensitic structure, which makes the blade exceptionally hard and brittle.

Understanding Carbon’s Role: Creating Hardness

Carbon plays a crucial role in determining the hardness and resilience of the Katana blade. As the steel heats up, the iron’s crystalline structure disintegrates, allowing carbon atoms to penetrate the gaps. When the blade is rapidly cooled, these carbon atoms remain locked within the iron lattice, creating a dense, hard structure.

If the cooling is too slow, the iron atoms reform their original structure, pushing carbon atoms out and making the steel softer and less durable. However, if cooled too quickly, the blade becomes excessively brittle, risking fractures during use. Therefore, the cooling speed must be perfectly balanced to ensure the blade's strength without sacrificing flexibility.

The Dangers of Incorrect Tempering

Improper tempering can lead to catastrophic failures:

-

Cracking: The most common issue, resulting from the stress of rapid cooling.

-

Warping: An uneven cooling rate can cause the blade to bend or distort.

-

Softness: If cooled too slowly, the blade will lack the necessary sharpness and rigidity.

-

Loss of Curvature: The sori (blade curve) may become more pronounced or flattened during the quenching process.

In some unfortunate cases, the blade may develop microscopic fractures that are not immediately visible but become apparent during subsequent use. These hidden weaknesses compromise the sword's structural integrity, making it unreliable in combat.

Secondary Tempering: Refining the Blade’s Characteristics

To mitigate the risks associated with the initial quenching, the blade undergoes a second tempering. This phase involves reheating the blade to a lower temperature, allowing the steel to relax and reduce internal stress. During this process, the Hamon (temper line) becomes visible.

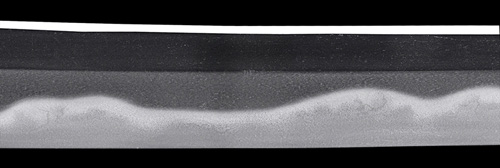

The Role of the Hamon

The Hamon is a wavy or straight line along the blade’s edge, resulting from the differential cooling process. It visually marks the transition between the hardened cutting edge and the softer spine. The Hamon is not only aesthetically significant but also indicates the quality and craftsmanship of the sword.

-

Formation: The blade is coated with a clay slurry of varying thickness. The thicker clay on the spine slows down cooling, while the thin layer on the edge allows rapid cooling, forming martensitic crystals only at the edge.

-

Aesthetic Patterns: Traditional patterns include Suguha (straight), Gunome (wavy), Choji (clove), and Notare (gentle wave).

-

Functional Purpose: The Hamon highlights the hard and soft regions of the blade, indicating where the sword can absorb shock versus where it cuts effectively.

Final Adjustments and Inspections

After tempering, the blade undergoes a series of inspections to detect any flaws. The swordsmith examines the curvature, hardness, and structural integrity. If the blade passes these tests, it moves to the polishing stage, where its surface is refined and the Hamon is highlighted.

Ensuring Longevity: Maintenance After Tempering

Proper maintenance is essential to preserve the tempered quality of the blade:

-

Regular Oiling: To prevent rust and oxidation.

-

Controlled Environment: Keeping the blade in a dry, cool place to avoid moisture damage.

-

Routine Inspections: Checking for any signs of warping or stress fractures.

The Hamon: Symbol of Craftsmanship and Functionality in Samurai Swords

The Hamon is one of the most distinctive and revered features of a traditional Samurai Katana. More than just an aesthetic line running along the blade, it embodies the artistic expression and technical expertise of the swordsmith. Formed during the tempering process (Yaki-Ire), the Hamon not only indicates the blade's hardness and cutting ability but also serves as a mark of authenticity and quality.

The Formation of the Hamon: A Complex Art

The creation of the Hamon begins with the Yaki-Ire process, a traditional tempering technique that carefully balances the blade's hardness and flexibility. After the initial forging and shaping, the entire blade is heated to a glowing red, signifying that it has reached the appropriate temperature for hardening. This stage is crucial because overheating can damage the blade’s molecular structure, while underheating may result in an edge that lacks durability.

Clay Application: The Secret to Differential Hardening

Before quenching, the swordsmith applies a clay mixture to the blade. This mixture is meticulously formulated, usually containing clay, charcoal, ash, and other mineral additives. The application of the clay is a delicate process, as its thickness and pattern will directly affect the Hamon's shape and consistency.

-

Thicker Clay on the Spine: This slows the cooling process, allowing the spine to remain soft and flexible.

-

Thinner Clay on the Edge: Encourages rapid cooling, making the cutting edge hard and sharp.

-

Artistic Patterns: Some smiths use artistic flair while applying the clay, creating unique and intricate Hamon designs.

Once the clay is applied, the blade is heated again, then quickly quenched in water or oil. The areas with thin clay cool rapidly, forming martensitic crystals, while the thicker clay areas cool more slowly, retaining pearlitic structure. This results in the contrasting hard edge and softer spine, essential for the Katana's legendary sharpness and resilience.

Hamon Patterns: Aesthetic and Functional Significance

The Hamon’s shape varies depending on the school of the swordsmith and the intended use of the blade. There are several traditional patterns, each representing not only an aesthetic choice but also a functional purpose:

1. Suguha (Straight Hamon)

-

A simple, straight line running along the blade.

-

Symbolizes refined simplicity and is often associated with early Samurai swords.

-

Provides a consistent cutting edge ideal for Iaido and Kenjutsu.

2. Gunome (Wavy Hamon)

-

Features wave-like patterns that resemble gentle ripples.

-

Balances hardness and flexibility, suitable for combat-ready swords.

-

Often seen on Katanas used in practical martial arts training.

3. Choji (Clove-Shaped Hamon)

-

Resembles a series of clove patterns, often rounded or curved.

-

Offers a highly artistic appearance, reflecting the aesthetic values of the Edo period.

-

Demonstrates the smith’s skill in controlling the clay application.

4. Notare (Undulating Hamon)

-

Characterized by smooth, rolling waves.

-

Subdivided into O-Notare (large waves) and Ko-Notare (small waves).

-

Combines elegance with durability, ideal for ceremonial swords.

5. Midare (Irregular Hamon)

-

An asymmetrical, chaotic pattern, often combining elements of Gunome and Choji.

-

Reflects the individuality of the swordsmith, making each blade unique.

-

Valued for its complexity and artistic expression

.

Figure 1 HAMON SHUGUA

Figure 2 HAMON GUNOME

Figure 3 HAMON NOTARE

Figure 4 HAMON CHOJI

Utsuri: The Shadow Hamon

In some of the finest Katanas, between the Hamon and the remaining blade surface, a faint, shadow-like line called Utsuri can appear. This phenomenon is caused by variations in the steel’s hardness, creating a subtle reflection or mirage.

-

Formation: Results from the tempering process and the layering technique.

-

Symbol of Quality: Often seen in antique Katanas and considered a mark of exceptional craftsmanship.

Polishing the Hamon: Revealing the Blade’s Soul

After the tempering process, the Hamon is not immediately visible. It emerges during the polishing stage, where skilled artisans use a series of whetstones, from coarse to fine, to gradually reveal the blade's natural beauty.

-

Stone Types: The final stages of polishing use Jizuya and Hazuya stones to accentuate the Hamon’s contrast.

-

Mirror Finish: The Hamon must be bright and reflective, highlighting the sharpness and quality of the blade.

-

Maintaining the Edge: Careful polishing ensures that the hard martensite layer remains intact, preserving the Katana's cutting capability.

Why the Hamon Matters: Tradition and Legacy

For collectors and martial artists alike, the Hamon is not just a decorative element but a testament to the swordsmith’s dedication. Its formation is a complex interplay of heat, cooling, and skill, representing centuries of refined technique passed down through generations.

A well-formed Hamon is an indication of a high-quality Katana, combining both aesthetic appeal and functional integrity. At YariNoHanzo, our Katanas showcase beautiful, authentic Hamon patterns, meticulously crafted using traditional techniques to honor the spirit of the Samurai.

Experience the excellence of Japanese craftsmanship and the beauty of the Hamon in every Katana from our collection. Discover why the Hamon remains a symbol of quality and tradition, revered by collectors and martial artists around the world.