How a Samurai sword (katana) is made

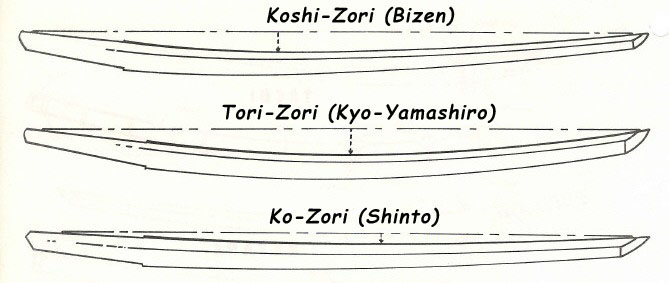

Typically, Katana blades measure approximately 60 to 75 cm in length, exhibiting a graceful and functional curve known as the sori. This curvature is not just an aesthetic feature but plays a crucial role in enhancing the blade's cutting efficiency. The curve allows the blade to slice smoothly through the target, as it naturally follows a flowing motion during the strike.

The sori is especially pronounced in older Katana models, primarily because these swords were often utilized by mounted warriors. The deeper curve made it more effective for delivering powerful cutting blows while on horseback, as it facilitated a smooth draw and fluid motion. This characteristic design element is a hallmark of traditional Samurai swords, reflecting the evolution of Japanese martial techniques and the practical needs of ancient warriors.

In addition to the distinctive curvature (sori), the geometry of a Katana blade plays a crucial role in defining its functionality, aesthetic appeal, and historical significance. The shape and structure of the blade often reflect the specific period in which the sword was crafted, as well as the practical needs of the warriors who wielded it. Understanding these variations is essential for both practitioners and collectors who appreciate the fine details of traditional Japanese craftsmanship.

Different eras and schools of sword-making developed unique geometric configurations to enhance the sword's performance for specific combat scenarios. Some designs prioritize cutting efficiency, while others focus on balance and durability. The geometry not only influences the sword's handling but also its suitability for various martial arts techniques.

Below, we present some of the most iconic and historically significant Katana models available in the YariNoHanzo catalogue, each reflecting the artistry and practical considerations of its time. These models exemplify the diversity and craftsmanship that define the legacy of Samurai swords.

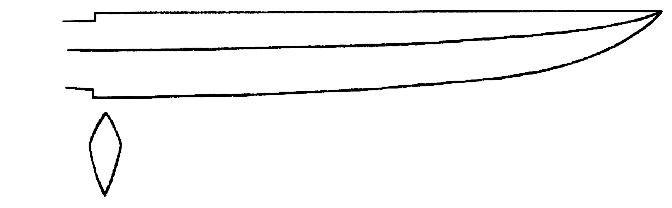

Hon-zukuri (or shinogi-zukuri):

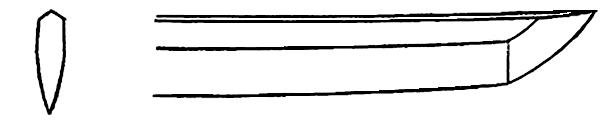

The Hon-zukuri, also known as Shinogi-zukuri, is one of the most widely recognized and traditional blade geometries found in Katana. This design is highly valued for its versatility, aesthetic appeal, and superior cutting performance.

Characterized by its elegantly curved profile, the Hon-zukuri blade features a distinct line called the yokote, which clearly marks the transition between the main blade and the tip (kissaki). Another key feature of this geometry is the shinogi, a raised ridge that runs parallel to the back of the blade (mune) and extends along its entire length. This ridge not only adds structural integrity to the blade but also contributes to its dynamic cutting ability, as it helps channel force during a strike.

The Hon-zukuri style emerged during the Heian period (794-1185), a time when the Samurai class was establishing its martial traditions. Due to its balance between sharpness and resilience, this blade design became immensely popular among Samurai warriors. The shinogi's raised spine allowed for both powerful cuts and precise thrusts, making it suitable for various combat scenarios.

Today, the Hon-zukuri remains one of the most iconic and functional blade shapes in the world of Japanese swords. Its harmonious blend of form and function exemplifies the artistry and ingenuity of traditional Japanese swordsmithing. Whether used in martial arts practice or displayed as a collector’s piece, the Hon-zukuri continues to symbolize the enduring legacy of the Samurai spirit.

Hira-zukuri (flat blade construction):

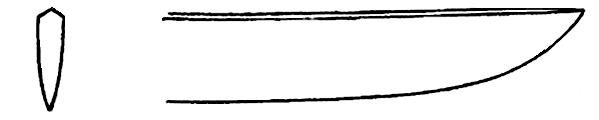

The Hira-zukuri is a distinctive blade geometry characterized by its flat, smooth surface on both sides of the blade. Unlike other traditional Katana styles, the Hira-zukuri does not feature a shinogi (raised ridge) or a yokote (line marking the transition to the tip). This absence of ridges and curves gives the blade a sleek, streamlined appearance, making it one of the most minimalist and elegant designs in Japanese sword craftsmanship.

This specific geometry is especially prevalent in Tanto blades, which are shorter Japanese swords or large daggers, commonly crafted after the Heian period (794-1185). The design's simplicity and lack of pronounced features make it ideal for smaller, more easily concealed blades. The flat construction also allows for an efficient and direct cutting motion, suitable for thrusting and quick, decisive strikes.

When the blade length exceeds 1.5 shaku (approximately 45 cm), it is referred to as O-Hira-zukuri. These longer versions maintain the same flat profile, but their increased length offers greater reach while preserving the characteristic smooth and unbroken surface.

The Hira-zukuri design is favored not only for its aesthetic simplicity but also for its practicality in close combat situations. The lack of a shinogi or yokote makes it lightweight and easy to handle, allowing for rapid movements and agile responses. While less common in full-length Katanas, this blade shape is highly respected in traditional Tanto crafting, highlighting its historical and functional significance.

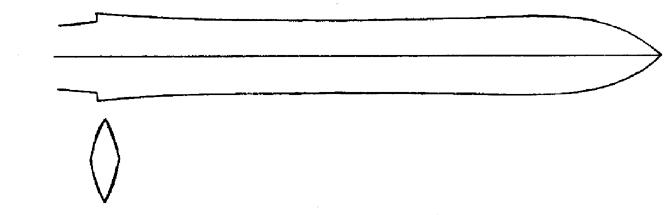

Shobu-zukuri (iris leaf constuction):

The Shobu-zukuri blade geometry is a unique and refined design, often associated with its resemblance to the shape of an iris leaf. This style is distinguished by its sleek, uninterrupted profile and is particularly favored for its practical efficiency in cutting and thrusting.

One of the defining features of the Shobu-zukuri is its continuous shinogi (raised ridge), which runs seamlessly from the base of the blade to the tip (kissaki). Unlike the more common Hon-zukuri style, the Shobu-zukuri lacks a distinct yokote (the line that separates the main blade from the tip). This absence of the yokote gives the blade a streamlined and unified appearance, which contributes to a more natural cutting motion and improved durability at the tip.

Historically, this blade geometry became particularly popular during the Muromachi period (1336-1573), a time marked by frequent conflicts and the need for robust, battle-ready swords. The Shobu-zukuri was commonly seen in shorter Japanese blades such as Tanto and Wakizashi, prized for their versatility and adaptability in close-quarters combat. The lack of a yokote reduces structural weakness at the tip, allowing for stronger, more resilient stabbing and slicing actions.

The term "Shobu" itself translates to "iris leaf" in Japanese, highlighting the blade's narrow, tapering shape that mimics the natural curve of an iris leaf. This design not only provides a visually appealing aesthetic but also offers a functional advantage, as the blade's profile is well-suited for piercing and cutting with minimal resistance.

Moroha-zukuri (double edge construction):

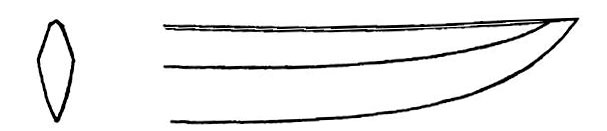

The Moroha-zukuri blade geometry is a unique and innovative design within the traditional Japanese swordsmithing repertoire. Unlike most Katana styles, which typically feature a single cutting edge, the Moroha-zukuri showcases a double-edged blade, offering a distinct combination of both versatility and effectiveness in combat.

This double-edged structure can present itself in both curved and straight configurations, making it adaptable for various fighting techniques. The shinogi (raised ridge) extends along the entire length of the blade, reaching the tip, similar to the Shobu-zukuri style. However, what sets the Moroha-zukuri apart is the absence of the yokote – the demarcation line that typically separates the blade from the tip. This lack of yokote gives the blade a continuous, flowing profile, enhancing its piercing capabilities while maintaining a sleek, balanced appearance.

Historically, the Moroha-zukuri design gained prominence during the Muromachi period (mid-15th century). This era was characterized by significant military activity and social upheaval, prompting swordsmiths to innovate and adapt traditional designs to meet the practical demands of warriors. The double-edged configuration proved advantageous in close combat, allowing for both slashing and thrusting maneuvers without needing to reposition the blade.

One of the most notable features of the Moroha-zukuri is its symmetrical cutting ability. Unlike single-edged Katana, where the practitioner must maintain blade orientation, the double-edged design permits efficient cuts from either side, enhancing the fluidity of movement and reducing the need for repositioning during fast-paced skirmishes.

The Moroha-zukuri’s versatility made it a popular choice for smaller blades, such as Tanto and Wakizashi, which required quick handling and the ability to perform both cutting and thrusting techniques. The balanced weight distribution and dual-edge sharpness made these blades exceptionally effective in fast, close-quarters combat.

Today, the Moroha-zukuri style continues to captivate martial artists and collectors for its practical design and historical significance.

Ken (Double-Edged Symmetrical Blade):

The Ken sword is one of the oldest and most distinctive forms of Japanese blades, characterized by its symmetrical double-edged construction. Unlike the curved and single-edged Katana typically associated with Samurai, the Ken features a straight, double-edged blade that maintains perfect symmetry along its central axis. This unique structure makes it fundamentally different from most traditional Japanese swords.

Dating back to ancient Japan, the Ken's origins can be traced to well before 700 A.C., making it one of the earliest known sword types in Japanese history. These blades are often associated with spiritual and ceremonial purposes rather than practical combat, although their form allows for both thrusting and cutting techniques.

The Ken's symmetrical profile is not only functional but also highly symbolic. Often linked to Buddhist rituals, these swords are revered as sacred objects and are sometimes found as offerings in temples or used as ritual implements. The blade's form, with equal cutting edges on both sides, represents balance, purity, and spiritual duality.

While the Ken's primary function was ceremonial, its design inherently supports efficient piercing and slashing, similar to the straight-edged double swords seen in other ancient cultures. Unlike curved blades that favor slicing motions, the Ken's straight design is ideal for direct and powerful thrusts, making it effective for penetrating armor when used in combat scenarios.

The craftsmanship involved in creating a Ken blade is meticulous, as maintaining symmetrical edges requires exceptional precision. The lack of curvature simplifies some forging aspects, but ensuring balance and equal sharpness on both sides remains a challenging task for skilled swordsmiths.

Today, Ken swords are cherished more as cultural artifacts and ceremonial pieces rather than practical weapons. They symbolize spiritual strength and are often displayed in shrines or used in religious ceremonies.

Balance and Weight of a Katana: Understanding the Dynamics

A well-crafted Katana is more than just a sharp blade; it is a masterpiece of balance and precision. One of the key aspects that define the functionality of a Katana is its center of gravity. In expertly balanced models, the center of gravity is typically located about 5-6 cm from the Tsuba (hand guard). However, in heavier or more robust variants, the center of gravity may shift forward to approximately 10-13 cm from the Tsuba.

This balance point significantly affects the sword’s handling characteristics. A forward-weighted Katana tends to generate more kinetic energy due to its increased inertia, resulting in greater cutting power. However, this also makes the sword less agile and more challenging to maneuver. Conversely, a backward counterbalance is generally more desirable, as it enhances the sword's responsiveness, making it quicker and easier to handle during fast-paced combat.

Weight Variations and Historical Context

Typically, a fully assembled Katana, including the hilt and Tsuba, weighs around 1 kg. However, weight variations exist depending on the specific model and historical period. Some heavier Katanas, especially those crafted during wartime, might weigh up to 1.2 kg, while lighter variants, such as some Shinto period examples, can weigh as little as 700 grams. The reason for these differences lies in the practical requirements of the era. During wars, heavier swords were often favored for their powerful strikes, while in times of peace, lighter, more agile swords were more practical.

A common misconception is that medieval Katanas—and even their Western counterparts—were excessively heavy and cumbersome. This notion is simply incorrect. In reality, historical blades, including large European swords, typically weighed between 1.1 kg to 1.7 kg. Even the infamous Zweihander, a massive two-handed sword used by a small number of heavily armored knights, rarely exceeded 2 kg. These larger swords were designed specifically to break through enemy pikes rather than for typical combat.

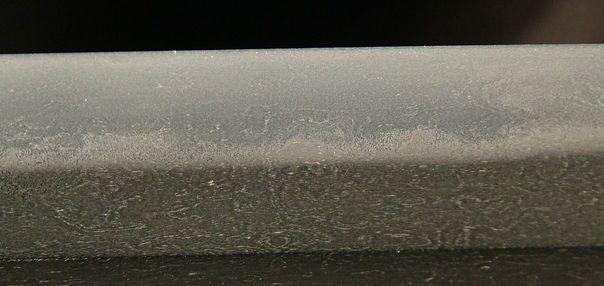

Examining the Hada of a Katana: Revealing the Intricate Patterns

To thoroughly observe and assess the Hada (grain pattern) on a Katana blade, it is essential first to remove the thin layer of oil that typically covers the surface. This oil is applied as a protective measure against rust and oxidation, but it can obscure the finer details of the Hada. Once the blade has been carefully cleaned and the metal surface is fully exposed, the intricate patterns become much more visible, allowing for detailed examination.

The Hada is a unique feature of traditionally forged Katanas, formed as a result of repeatedly folding and hammering the steel during the forging process. This meticulous craftsmanship results in patterns that resemble natural wood grain, often with interwoven lines and dots. The appearance of Hada varies depending on the specific forging techniques used and the quality of the raw materials.

Types of Hada: Itame and Masame

One of the most visually striking Hada patterns is a combination of Itame and Masame, which are two distinct grain types. Itame refers to a pattern that resembles flowing, irregular wood grain, often with rounded, swirling lines. In contrast, Masame presents straight, linear patterns similar to the grain seen in long, straight pieces of wood. When combined, these patterns create a visually dynamic effect, reminiscent of the natural textures found in tree bark or hardwood.

The subtle blend of these two types of Hada not only adds aesthetic value but also indicates the craftsmanship of the swordsmith. The pattern’s uniformity and clarity are indicators of high-quality forging, where the folding process has been executed with precision. Such a combination is not merely decorative; it is a testament to the skill involved in creating a blade that is both functional and visually stunning.

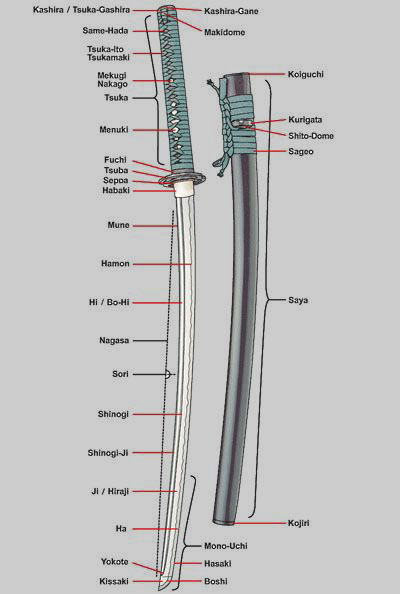

The Koshirae: The Sword’s Elegant Mounting

Apart from the blade itself, a traditional Katana includes carefully crafted components collectively known as Koshirae. This mounting is essential not just for aesthetic appeal but also for functional protection and handling. The Koshirae consists of:

-

Tsuka (Handle): The grip of the sword, usually wrapped in ray skin (same) and cord, providing both comfort and secure handling.

-

Tsuba (Hand Guard): A protective guard between the blade and handle, often ornately decorated, serving both as a hand protector and a balancing element.

-

Habaki (Blade Collar): A metal piece, typically made of copper, that fits around the base of the blade near the Tsuba. It secures the blade within the scabbard (Saya) and helps distribute the force of impact when striking.

Craftsmanship and Precision

Japanese artisans have long recognized the importance of every minor detail in a Katana. Even the smallest components are crafted with care and precision, reflecting the philosophy that the sword is more than just a weapon; it is an extension of the Samurai’s spirit. The naming convention of each part of the Katana highlights the cultural significance and meticulous attention given to every detail.

To truly appreciate the artistry behind a Samurai sword, one must consider not only the blade itself but the complete assembly of its parts. The Hada and Koshirae together represent the harmony of strength, beauty, and craftsmanship, encapsulating the essence of the Samurai tradition.

At YariNoHanzo, we are dedicated to preserving the authenticity and legacy of traditional Japanese sword-making. Our collection features Katanas with beautifully crafted Hada patterns and complete Koshirae, ensuring that each piece is not only a weapon but a work of art. Explore our selection and discover the perfect blend of heritage and precision.

The Evolution of Tsuba: From Functional Simplicity to Ornate Artistry

In the early history of Japanese sword-making, the Tsuba (hand guard) was primarily a functional component, designed to protect the wielder’s hand from sliding onto the blade during combat. Typically made from iron or simple alloys, ancient Tsuba were often plain, unadorned, and strictly utilitarian. Their design focused on durability and practicality rather than aesthetic appeal, as the primary purpose of the Katana during this period was combat effectiveness.

However, as Japan transitioned from centuries of warfare to a more peaceful era under the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603–1868), the role of the Tsuba began to evolve significantly. With the unification of Japan and the establishment of a stable, centralized government, the Samurai class gradually shifted from active warriors to social elites and bureaucrats. As a result, the Katana transformed from a weapon of war into a symbol of status and personal refinement.

This societal change led to the Tsuba becoming more than just a protective element; it became an opportunity for artistic expression. Skilled craftsmen started creating elaborate and intricately decorated Tsuba, using techniques such as inlaying, engraving, and carving. These guards featured detailed motifs inspired by nature, folklore, and cultural symbols, reflecting both the personal tastes of the Samurai and the aesthetic values of the time.

The materials used in Tsuba production also diversified, incorporating precious metals like gold, silver, and copper, as well as sophisticated alloys such as shakudo (a copper and gold mix that develops a dark patina). The craftsmanship of a Tsuba could reflect the owner's rank, wealth, and artistic sensibility, making it a central element of a Samurai’s ceremonial attire.

During the Edo period, collecting and commissioning unique Tsuba became a popular hobby among the Samurai and nobility. The intricacy of a Tsuba's design was not only a matter of personal pride but also a reflection of the Samurai’s cultural sophistication and social standing. A well-crafted Tsuba became a conversation piece and a symbol of heritage, often passed down through generations as a treasured heirloom.

The Tsuka: Craftsmanship and Functionality of the Katana Handle

The Tsuka (handle) of a Katana is meticulously crafted to ensure both durability and comfort, tailored specifically to each individual blade. Unlike mass-produced sword handles, the Tsuka is designed to perfectly complement the balance and feel of the blade, enhancing the overall handling experience.

Materials and Construction

The core of the Tsuka is typically made from high-quality hardwood, chosen for its strength and ability to absorb shock. To further enhance the grip, the wooden core is meticulously wrapped with ray skin (Same). This unique material not only adds a textured surface that prevents slipping but also reinforces the handle’s structure, making it resilient against stress and prolonged use.

Over the ray skin, a cord wrap known as Tsuka-Ito is tightly woven, usually made from silk, cotton, or leather. This intricate braiding technique is not just for aesthetic purposes; it serves to secure the underlying layers and provide a comfortable yet firm grip. The traditional weaving pattern is carefully executed to ensure consistency and balance, allowing the user to maintain control during swift movements and powerful strikes.

Secure Fit with Mekugi

One of the most critical elements in the Tsuka’s construction is the use of Mekugi—small pegs usually made from resilient bamboo. The tang of the blade (Nakago) contains pre-drilled holes, which are precisely aligned with corresponding holes on the Tsuka. The Mekugi are inserted through these holes to firmly anchor the blade to the handle, preventing any separation even under intense force.

The choice of bamboo for the Mekugi is intentional, as its natural fibrous structure allows for slight compression and expansion, maintaining a secure fit over time. In the unlikely event of a breakage, the splintered bamboo tends to lodge between the tang and the Tsuka, keeping the blade from dislodging. This ingenious feature ensures safety during practice and combat, showcasing the practical ingenuity of traditional Japanese craftsmanship.

Functionality and Ergonomics

The ergonomic design of the Tsuka plays a vital role in the functionality of the Katana. Its shape and texture are crafted to soften the impact of strikes, distributing force evenly along the handle. This design reduces hand fatigue and increases the wielder’s efficiency in prolonged practice or real combat scenarios.

A properly wrapped Tsuka also serves as a tactile guide, helping the Samurai instinctively know the blade orientation without looking. This is essential for precise cuts and seamless transitions between techniques. The symmetrical design of the Tsuka ensures that the grip remains secure and consistent, regardless of the fighting style employed.

Symbolism and Aesthetics

Beyond its practical aspects, the Tsuka also holds symbolic value. The way it is wrapped and decorated often reflects the personal taste and rank of the Samurai, making it not just a functional component but a representation of identity and craftsmanship. Some handles feature ornate Menuki (decorative metal fittings) placed under the cord wrap, adding both visual appeal and a textured grip for the fingers.

Fuchi-Kashira: The Ornamental and Functional End Caps of the Tsuka

The Fuchi-Kashira are essential components of the Katana’s Tsuka (handle), serving both functional and decorative purposes. These elements not only secure the handle components but also add a touch of artistic elegance, reflecting the craftsmanship and aesthetic sensibility of traditional Japanese swordsmiths.

Structure and Placement

The Fuchi is a small, intricately designed metal cylinder located at the point where the Tsuka meets the Tsuba (hand guard). It acts as a reinforcing collar, ensuring that the handle remains firmly attached to the blade. The Fuchi plays a vital role in maintaining the structural integrity of the sword, as it absorbs some of the shock generated during strikes and prevents the Tsuka from loosening over time.

On the opposite end of the handle, you will find the Kashira. This piece is also a cylindrical metal cap but is closed at one end, functioning as a handle stopper. The Kashira ensures that the Tsuka-Ito (handle wrap) remains securely in place, preventing the cord from unraveling and maintaining the grip’s stability.

Unified Design and Balance

Together, the Fuchi and Kashira form a matched set, often designed to complement each other visually and thematically. This pairing not only balances the look of the handle but also contributes to the Katana’s harmonious aesthetic. The consistency in design between these two components symbolizes the balance between the sword’s power and the wielder’s control.

Artistic Significance

Historically, the Fuchi-Kashira sets were crafted with great attention to detail, often decorated with motifs reflecting the Samurai’s rank, family crest (Mon), or personal beliefs. The designs range from simple, understated patterns to elaborate carvings depicting mythological creatures, natural scenes, or symbolic patterns.

The decoration is typically done through engraving, inlaying, or relief work, using a variety of metals like iron, copper, shakudo (a copper-gold alloy), or even gold and silver. These materials not only add aesthetic value but also enhance the durability of the components.

Functional Durability

Beyond their decorative appeal, both the Fuchi and Kashira serve crucial practical functions. The Fuchi acts as a shock absorber, dispersing the impact generated during cutting or blocking, thus protecting the handle from splitting. Meanwhile, the Kashira ensures that the end of the Tsuka remains secure and stable, especially during intense practice or combat. The use of robust metals in their construction makes them resistant to wear, maintaining the Katana’s integrity over time.

Symbolism and Craftsmanship

The Fuchi-Kashira combination is more than just a structural necessity; it represents the unity and strength of the blade and handle. In traditional Japanese craftsmanship, the balance between beauty and utility is paramount, and the Fuchi-Kashira perfectly encapsulates this philosophy. Their design reflects not only the artisan’s skill but also the Samurai’s dedication to harmony and precision.

The Habaki: Function and Design of the Katana’s Blade Collar

The Habaki is a fundamental component of the Katana, typically crafted from copper or brass. Positioned at the base of the blade, just above the Tsuba (hand guard), the Habaki serves several essential functions, both practical and structural. Despite its small size, it plays a crucial role in maintaining the stability and integrity of the entire sword.

Multifunctional Design

One of the primary functions of the Habaki is to secure the blade within the Saya (scabbard). When the Katana is sheathed, the Habaki fits snugly into the Saya’s opening, creating a tight friction fit that prevents the blade from sliding out accidentally. This ensures that the sword remains safely in place during movement, whether in practice, transport, or display.

Additionally, the Habaki acts as a shock absorber, distributing the impact force from cuts or thrusts to reduce stress on the Tsuka (handle). This helps maintain the structural integrity of the Katana, especially during rigorous use. By transmitting a portion of the shock to the handle, the Habaki reduces the risk of damage to the blade and the handle junction, preserving the sword’s durability.

Another critical function of the Habaki is to protect the blade from rust and moisture. Since the base of the blade is particularly vulnerable to corrosion, the tightly fitted Habaki forms a seal when the Katana is housed in the Saya, minimizing exposure to air and humidity. This simple yet effective design helps prolong the lifespan of the blade by preventing rust formation.

Symbolism and Aesthetics

While primarily functional, the Habaki also holds aesthetic value. Some are plain and utilitarian, while others feature engraved patterns or decorative motifs, reflecting the swordsmith’s craftsmanship and the Samurai’s status. The choice of material and finish often correlates with the overall design theme of the sword, harmonizing with elements like the Fuchi, Kashira, and Tsuba.

The Saya: Protective and Ornamental Scabbard

The Saya is the traditional wooden scabbard that houses the blade. Typically made from lacquered wood, the Saya not only protects the Katana from environmental damage but also enhances the sword’s aesthetic appeal. The lacquer coating adds a glossy finish that is both visually striking and resistant to moisture.

Menuki: Functional and Decorative Enhancements

Embedded within the Tsuka (handle) and positioned under the Tsuka Ito (braided silk wrap), the Menuki serve a dual purpose. These small metal ornaments are not just for decoration; they are strategically placed to enhance the grip by providing a tactile reference for hand positioning. This ensures that the wielder instinctively knows the correct orientation of the blade, even without looking.

The Menuki are often crafted with great attention to detail, featuring ornamental designs inspired by nature, mythology, or family crests. These motifs are not only visually appealing but also culturally significant, often reflecting the Samurai’s lineage or personal beliefs. In many cases, the Menuki’s design matches the overall theme of the sword’s fittings, such as the Fuchi and Kashira, creating a cohesive and harmonious aesthetic.

Balancing Function and Artistry

Both the Habaki and Menuki exemplify the perfect balance between functionality and artistry that defines traditional Japanese sword-making. The Habaki ensures blade stability, rust protection, and shock absorption, while the Menuki provide grip enhancement and visual elegance. Together, these elements contribute to the overall harmony of the Katana, making it not only a weapon but a work of art.

The Sageo: Multifunctional Cord of the Katana Scabbard

The Sageo is an essential accessory for the Katana, serving both functional and aesthetic purposes. It is a durable, woven cord, typically made from silk, cotton, or synthetic fibers, and comes in various lengths and colors. Traditionally, the Sageo is wrapped around the Saya (scabbard) and secured with a complex knot, creating a visually appealing and highly functional element of the sword.

Practical Uses of the Sageo

The primary purpose of the Sageo is to secure the Saya to the Samurai’s Obi (belt) during practice or in combat. This ensures that the scabbard remains firmly in place, allowing for quick and efficient drawing of the blade. The method of tying the Sageo can vary depending on the martial art practiced or the specific requirements of the swordsmanship style.

Apart from its role in securing the sword, the Sageo also functions as a decorative element, showcasing the sword owner's personal style and the craftsmanship involved. The intricate knotting techniques used to bind the Sageo to the Saya are often passed down through generations, each knot symbolizing a unique cultural or martial tradition.

Tying Techniques and Styles

There are numerous ways to tie the Sageo, ranging from simple, practical knots to elaborate, ceremonial bindings. One of the most common methods is the "Warrior’s Knot", designed for practicality and quick release. In contrast, more decorative knots, such as those used in ceremonial or display settings, are often intricate and symmetrical, highlighting the aesthetic aspect of the Katana.

Some schools of Iaido and Kenjutsu teach specific ways of knotting the Sageo that align with their training philosophy. These methods are not just for appearance but also serve a tactical purpose, allowing the practitioner to untie or adjust the Sageo with minimal effort during training or combat.

Symbolism and Cultural Significance

The way a Sageo is tied can convey a Samurai's status, school affiliation, or even personal philosophy. In some traditions, the knot style could indicate whether the Samurai was at peace or prepared for battle. Additionally, the choice of material and color can carry symbolic meaning, often reflecting the wearer’s rank or clan identity.

Maintenance and Care

To maintain its functionality and appearance, the Sageo should be kept clean and properly tied. Regular adjustments help prevent it from becoming loose or worn. Due to its frequent use, especially during martial arts practice, it is essential to periodically check the knot’s integrity and the condition of the material. High-quality Sageo made from silk or cotton tends to last longer and maintains a more refined appearance compared to synthetic alternatives.

Aesthetic Contribution

Beyond its practical applications, the Sageo adds a visual balance to the Katana’s overall presentation. The intricate patterns and contrasting colors can complement the design of the Saya, enhancing the elegance and symmetry of the sword when displayed. Whether wrapped tightly around the scabbard or hanging loosely, the Sageo’s presence completes the traditional look of a properly mounted Katana.

Shirasaya: The Traditional Resting Mount for the Katana

The Shirasaya (literally meaning "white scabbard") is a minimalist and elegant form of sword mounting, primarily designed for the preservation of the blade rather than combat use. Unlike the more elaborate and decorated Koshirae used for combat, the Shirasaya consists of a simple wooden handle (Tsuka) and scabbard (Saya), both crafted from plain, unadorned wood, usually magnolia. This understated design serves a crucial function in maintaining the blade’s condition over extended periods of inactivity.

Purpose and Design of the Shirasaya

The Shirasaya is specifically created to store and protect the blade when it is not actively used or displayed in a combat-ready mounting. The wood used is carefully selected for its non-abrasive and moisture-absorbing qualities, which help prevent rust and corrosion on the finely polished steel. The interior of the Shirasaya is left untreated to avoid trapping moisture, allowing the blade to "breathe" and remain dry.

One of the primary advantages of the Shirasaya is its ease of disassembly and cleaning. The simplistic construction allows for quick removal of the blade, making it convenient for periodic maintenance. This characteristic is particularly beneficial when the Katana is stored for long periods, as it minimizes the risk of deterioration.

Historical Significance and Usage

While the Shirasaya is not intended for combat, there are historical instances where Samurai used swords mounted in Shirasaya during emergencies. However, this was uncommon, as the lack of a hand guard (Tsuba) made it impractical for proper swordsmanship. Typically, the Shirasaya was a resting mount, crafted specifically to preserve blades when they were not actively needed.

Traditionally, when a Katana had served its purpose for around 200 years, it was often placed into a Shirasaya for long-term preservation. This practice honored the blade’s legacy, allowing it to be passed down through generations without risking damage from exposure or improper storage. The Shirasaya thus became synonymous with respect for the sword’s history and craftsmanship.

Craftsmanship and Customization

Each Shirasaya is custom-made to fit the specific blade it houses, ensuring a snug and secure fit. The handle and scabbard are crafted from the same piece of wood, creating a seamless and unified appearance. The lack of ornate fittings highlights the natural beauty of the wood grain, emphasizing the concept of simplicity and elegance.

Often, the Shirasaya is inscribed with the blade’s signature (Mei) on its surface, providing important historical information without detracting from its minimalist appeal. This inscription ensures that even when the blade is in storage, its identity and heritage are preserved.

Shirasaya as a Symbol of Rest

The philosophy behind the Shirasaya is deeply rooted in the idea of allowing the blade to rest after years of active use. When a Samurai sword had fulfilled its duty, it was placed in the Shirasaya as a gesture of respect and preservation. The simplicity of this mounting underscores the reverence for the blade’s craftsmanship and history.

Modern Use and Display

Today, the Shirasaya is still widely used for sword storage and display. Its clean lines and understated design make it ideal for collectors who appreciate the aesthetic purity of a blade without the distraction of ornate fittings. Moreover, it is favored by sword enthusiasts who value the authentic preservation methods passed down through generations.

The Traditional Way of Wearing a Katana: Edge Upwards

One of the most distinctive aspects of the Samurai’s attire is the way the Katana is worn. Traditionally, the Katana is tucked into the Obi (belt) with the edge facing upwards. This specific orientation is not only visually striking but also highly functional, reflecting the practical mindset of the Samurai class.

Practical Benefits of Edge-Up Carry

The primary reason for positioning the blade with the edge facing upwards is to protect the cutting edge from unnecessary wear and damage. When the blade rests with the sharp edge upward, it is less likely to rub against the interior of the Saya (scabbard) during movement. This method significantly reduces the risk of dulling the blade, preserving its sharpness and cutting efficiency over time.

Moreover, this upward position facilitates a swift and fluid drawing motion. During a combat scenario, the Samurai could easily grip the Tsuka (handle) with one hand while pushing the Saya with the other, allowing the blade to be unsheathed in one smooth, controlled motion. This technique, known as Iaijutsu, is the art of drawing the sword and cutting simultaneously, a skill essential for quick and decisive actions.

Strategic and Tactical Considerations

Wearing the Katana with the cutting edge facing upward also allows for more precise control when initiating an attack. As the sword is drawn, the blade naturally follows the line of the Samurai’s arm, making it possible to strike in a single motion without repositioning. This strategic advantage can mean the difference between life and death in a sudden confrontation.

Furthermore, the edge-up orientation also aids in defensive maneuvers. When drawn correctly, the blade can be positioned for an immediate block or parry, making it an integral part of close-quarters combat techniques. This efficiency in motion underscores the practical wisdom behind the traditional way of carrying the Katana.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance

Beyond practicality, the way the Katana is worn also carries symbolic meaning. It reflects a state of readiness and respect, as the Samurai is always prepared to respond to danger while also demonstrating proper etiquette by not displaying the blade openly. This balance between being prepared and showing restraint aligns with the Bushido code, emphasizing discipline and honor.

Modern Practice

Today, practitioners of Iaido and Kenjutsu continue to wear the Katana in this traditional manner during training and demonstrations. Maintaining the edge-up position is crucial not only for authenticity but also for practical training, as it helps students master the art of rapid drawing and precise cutting.